A Kentucky county nestled in the heart of Appalachia, where the opioid crisis has wreaked devastation for decades, spent $15,000 of its opioid settlement money on an ice rink.

That amount wasn’t enough to solve the county’s troubles, but it could have bought 333 kits of Narcan, a medication that can reverse opioid overdoses. Instead, people are left wondering how a skating rink addresses addiction or fulfills the settlement money’s purpose of remediating the harms of opioids.

Like other local jurisdictions nationwide, Carter County is set to receive a windfall of more than $1 million over the next decade-plus from companies that sold prescription painkillers and were accused of fueling the overdose crisis.

County officials and proponents of the rink say offering youths drug-free fun like skating is an appropriate use of the money. They provided free entry for students who completed the Drug Abuse Resistance Education (D.A.R.E.) curriculum, recovery program participants, and foster families.

But for Brittany Herrington, who grew up in the region and became addicted to painkillers that were flooding the community in the early 2000s, the spending decision is “heartbreaking.”

“How is ice-skating going to teach [kids] how to navigate recovery, how to address these issues within their home, how to understand the disease of addiction?” said Herrington, who is now in long-term recovery and works for a community mental health center, as well as a regional coalition to address substance use.

She and other local advocates agreed that kids deserve enriching activities, but they said the community has more pressing needs that the settlement money was intended to cover.

Carter County’s drug overdose death rate consistently surpasses state and national averages. From 2018 to 2021, when overdose deaths were spiking across the country, the rate was 2.5 times as high in Carter County, according to the research organization NORC.

Other communities have used similar amounts of settlement funding to train community health workers to help people with addiction, and to buy a car to drive people in recovery to job interviews and doctors’ appointments.

Local advocates say $15,000 could have expanded innovative projects already operating in northeastern Kentucky, like First Day Forward, which helps people leaving jail, many of whom have a substance use disorder, and the second-chance employment program at the University of Kentucky’s St. Claire health system, which hires people in recovery to work in the system and pays for them to attend college or a certification program.

“We’ve got these amazing programs that we know are effective,” Herrington said. “And we’re putting an ice-skating rink in. That’s insane to me.”

A yearlong investigation by KFF Health News, along with researchers at the Johns Hopkins University Bloomberg School of Public Health and the national nonprofit Shatterproof, found many jurisdictions spent settlement funds on items and services with tenuous, if any, connections to addiction. Oregon City, Oregon, spent about $30,000 on screening first responders for heart disease. Flint, Michigan, bought a nearly $10,000 sign for a community service center building , and Robeson County, North Carolina, paid about $10,000 for a toy robot ambulance.

Although most of the settlement agreements come with national guidelines explaining the money should be spent on treatment, recovery, and prevention efforts, there is little oversight and the guidelines are open to interpretation.

A Kentucky law lists more than two dozen suggested uses of the funds, including providing addiction treatment in jail and educating the public about opioid disposal. But it is plagued by a similar lack of oversight and broad interpretability.

Chris Huddle and Harley Rayburn, both of whom are elected Carter County magistrates who help administer the county government, told KFF Health News they were confident the ice rink was an allowable, appropriate use of settlement funds because of reassurances from Reneé Parsons, executive director of the Business Cultivation Foundation. The foundation aims to alleviate poverty and related issues, such as addiction, through economic development in northeastern Kentucky.

The Carter County Times reported that Parsons has helped at least nine local organizations apply for settlement dollars. County meeting minutes show she brought the skating rink proposal to county leaders on behalf of the city of Grayson’s tourism commission, asking the county to cover about a quarter of the project’s cost.

In an email, Parsons told KFF Health News that the rink — which was built in downtown Grayson last year and hosted fundraisers for youth clubs and sports teams during the holiday season — serves to “promote family connection and healing” while “laying the groundwork for a year-round hockey program.”

“Without investments in prevention, recovery, and economic development, we risk perpetuating the cycle of addiction in future generations,” she added.

She said the rink, as well as an $80,000 investment of opioid settlement funds to expand music and theater programs at a community center, fit with the principles of the Icelandic prevention model, “which has been unofficially accepted in our region.”

That model is a collaborative community-based approach to preventing substance use that has been highly effective at reducing teenage alcohol use in Iceland over the past 20 years. Instead of expecting children to “just say no,” it focuses on creating an environment where young people can thrive without drugs.

Part of this effort can involve creating fun activities like music classes, theatrical shows, and even ice-skating. But the intervention also requires building a coalition of parents, school staffers, faith leaders, public health workers, researchers, and others, and conducting rigorous data collection, including annual student surveys.

About 120 miles west of Carter County, another Kentucky county has for the past several years been implementing the Icelandic model. Franklin County’s Just Say Yes program includes more than a dozen collaborating organizations and an in-depth annual youth survey. The project began with support from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and has also received opioid settlement dollars from the state.

Parsons did not respond to specific questions about whether Carter County has taken the full complement of steps at the core of the Icelandic model.

If it hasn’t, it can’t expect to get the same results, said Jennifer Carroll, a researcher who studies substance use and wrote a national guide on investing settlement funds in youth-focused prevention.

“Pulling apart different elements, at best, is usually going to waste your money and, at worst, can be counterproductive or even harmful,” she said.

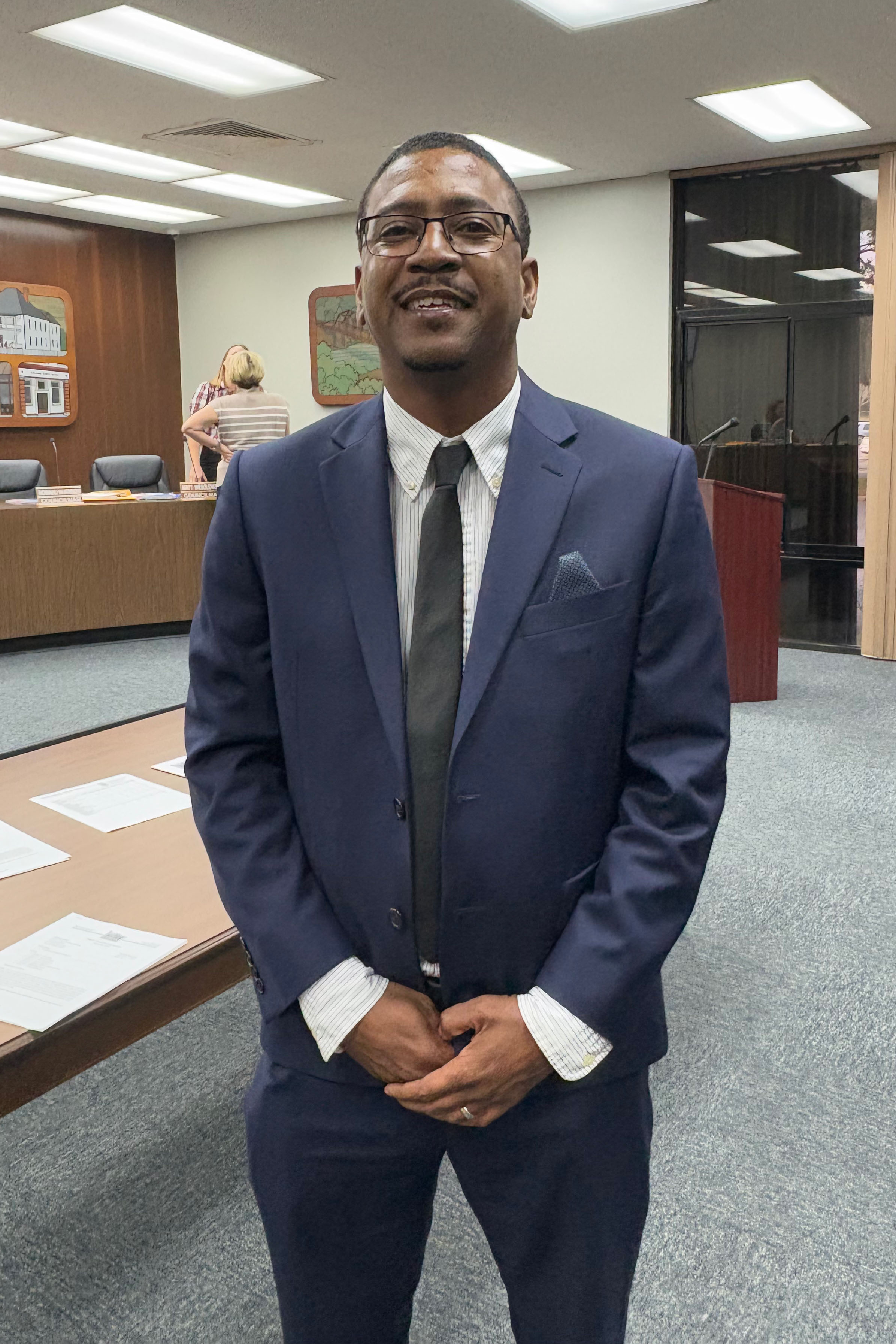

At least one Carter County magistrate has come to regret spending settlement funds on the skating rink.

Millard Cordle told KFF Health News that, after seeing the rink operate over the holidays, he felt it was “a mistake.” Although younger children seemed to enjoy it, older kids didn’t engage as much, nor did it benefit rural parts of the county, he said. In the future, he’d rather see settlement money help get drugs off the street and offer people treatment or job training.

“We all learn as we go along,” he said. “I know there’s not an easy solution. But I think this money can help make a dent.”

As of 2024, Carter County had received more than $630,000 in opioid settlement funds and was set to receive more than $1.5 million over the coming decade, according to online records from the court-appointed settlement administrator.

It’s not clear how much of that money has been spent, beyond the $15,000 for the ice rink and $80,000 for the community arts center.

It’s also uncertain who, if anyone, has the power to determine whether the rink was an allowable use of the money or whether the county would face repercussions.

Kentucky’s Opioid Abatement Advisory Commission, which controls half the state’s opioid settlement funds and serves as a leading voice on this money, declined to comment.

Cities and counties are required to submit quarterly certifications to the commission, promising that their spending is in line with state guidelines. However, the reports provide no detail about how the money is used, leaving the commission with little actionable insight.

At a January meeting, commission members voted to create a reporting system for local governments that would provide more detailed information, potentially opening the door to greater oversight.

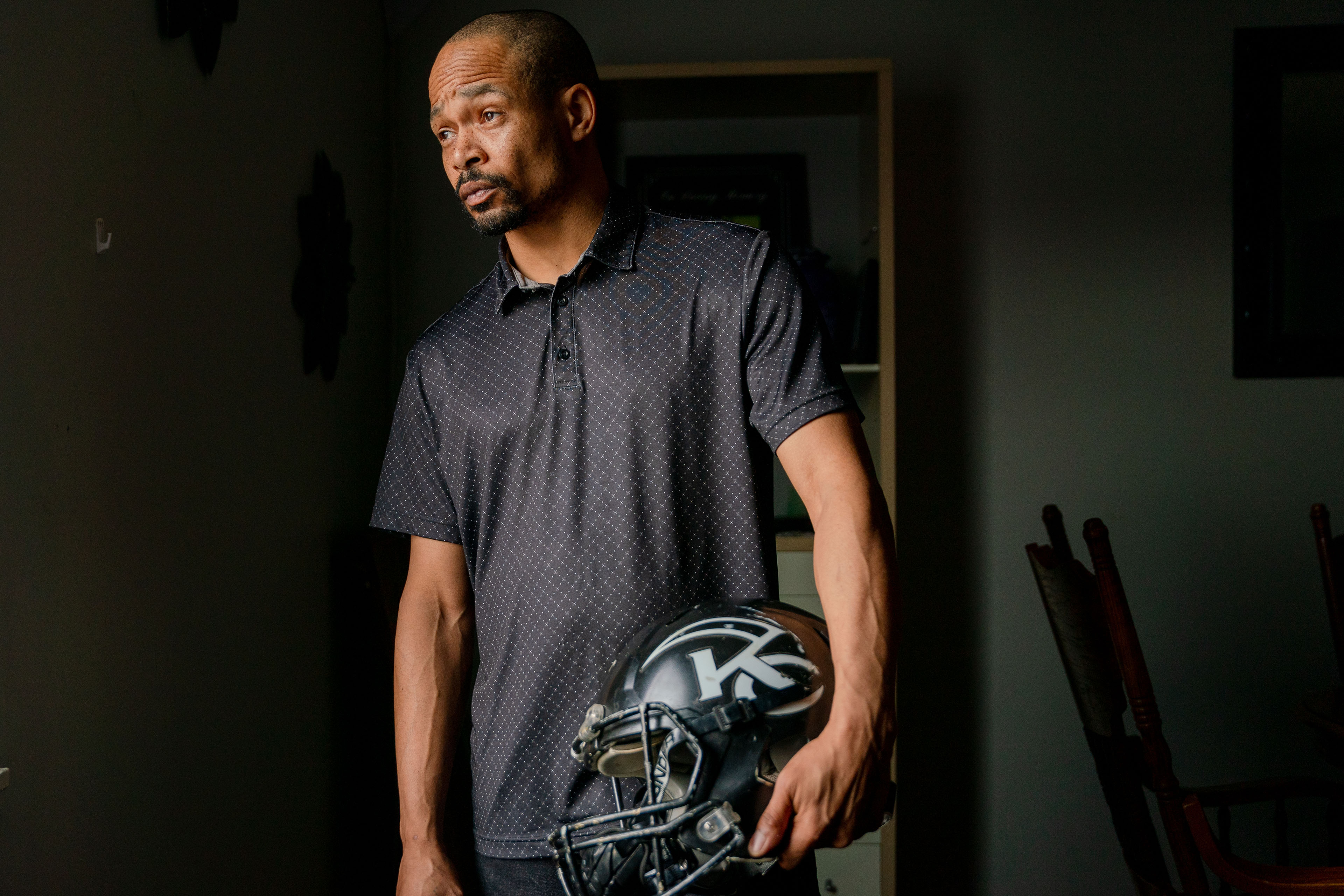

That would be a welcome change, said John Bowman, a person in recovery in northeastern Kentucky, who called the money Carter County spent on the ice ink “a waste.”

Bowman works on criminal justice reform with the national nonprofit Dream.org and encounters people with substance use disorders daily, as they struggle to find treatment, a safe place to live, and transportation. Some have to drive over an hour to the doctor, he said — if they have a car.

He hopes local leaders will use settlement funds to address problems like those in the future.

“Let’s use this money for what it’s for,” he said.

KFF Health News is a national newsroom that produces in-depth journalism about health issues and is one of the core operating programs at KFF—an independent source of health policy research, polling, and journalism. Learn more about KFF.

USE OUR CONTENT

This story can be republished for free (details).

from KFF Health News https://ift.tt/LPikN0Z

Rose

Rose