The Martian would be wrong.

The trial that has cardiologists across the land choking back tears is a hypertension study done in black barbershops. The idea is fairly simple. Black men have the highest rates of disability related to uncontrolled hypertension, in large part related to a difficulty in engaging black men with the health care system. The end result of poorly controlled hypertension in this community was on full display where I did much of my medical training as a student and resident in the heart of North Philadelphia. Ensconced in the walls of Temple we learned to manage the end organs ravaged by hypertension. I have to say I never stopped to think what we could have done to interrupt this process even though we were located in the heart of an underserved black community.

Luckily, Ronald Victor has been thinking about this problem for some time. A Cedars Sinai physician, his research focuses on community interventions to rectify health care disparities. His first study in 2007 sought to examine the feasibility of blood pressure screenings in black barbershops because this was where black men congregated and may be susceptible to influence by important peer influencers: barbers.

The 2007 study by Victor proved that it was feasible to enlist barbers to measure blood pressures, correctly stage hypertension, and make a referral to a clinician for treatment. This opened up funding for the next step in the process- actually affect blood pressure control in barbershops. The trial was wildly positive. In stark contrast to the multibillion dollars of research that lead to a $1000/month PCSK9 inhibitor that gives us a 15% relative risk reduction of a composite outcome of stroke/death/heart attack, the Victor barbershop protocol resulted in a staggering average 27mmHg blood pressure drop in 6 months. The potential ramifications are large for a 20mmHg drop – a 30% reduction in risk of a heart attack or a 40% reduction in risk of a stroke.

This type of low tech intervention is catnip for a public health community committed to the idea that the health of the individual is a function of the structural determinants and conditions in which people are born, grow, live, work and age. This is what is supposed to lie at the heart of the zipcode disparity that results in healthcare outcomes frustratingly equivalent or worse compared to the rest of the world despite per capita spending that is multiples of other developed countries.

If America is to have better average health at low cost, it will not be achieved by the 70 year old heart attack survivor being prescribed the latest $1000/month lipid lowering agent, or by Starbucks latte sipping 55 year olds with a fitbit, but with low tech nudges to poorly performing communities.

The barbershop intervention would seem to be the anecdotal trial that proves the social determinants of health principle – design a healthcare system focused not on the fire burning the house down, but on flame retardant construction material.

I read the trial as a hopeful skeptic because of my failure with patients like Harry White.

The most striking aspect of Harry is his size – six foot five, three hundred and thirty pounds. I met him 5 years ago after he had suffered a small stroke. An echocardiogram had revealed a weak heart, with a blood clot comfortably nestled at the apex. The weak heart was thought to be related to uncontrolled hypertension that he freely admitted he had sought no treatment for in years. He had no insurance, but he had some help. He was plugged into a health center that would help him get blood work and medications for free, and I offered to see him in my clinic without insurance to manage his hypertension and heart failure. He made a few visits to my office over the next year – but then disappeared, only to emerge 4 years later again off of all of his medications. My attempts to find out what would help him return to the office more regularly were spectacularly unsuccessful.

The thing with Harry that was especially frustrating was that his healthcare access problem was a self made one. He had a good, motivated young physician working for him at a federally qualified health care center who worked to get all his medications for him at no cost, and perhaps somewhat less importantly had easy access to see a cardiologist as well. He had on a pair of new jeans, an untucked and oversized button down shirt as is the fashion, a pair of barely worn sneakers, and a big silver framed watch, all of which projected a man who had things under control.

Yet when Harry spoke, he spoke of a system that controlled him. My office wouldn’t give him an appointment (he never called and didn’t want to make one while he was in the office), his primary wouldn’t fill out a form to allow him to return to his prior job (the form was filled out multiple times), and he couldn’t afford his medications (his primary would get him medications for free). It was like he was living in an alternate reality. A broad coalition waits for Harry to reach out. He seldom did. This disengagement, this idea that every problem is a creation of someone else, is widespread. The McSalad Shaker must have disappeared from the McDonalds menu because a high level executive didn’t get the memo about featuring only unhealthy choices to poor communities, not because consumers avoided picking the option. This may also explain why I have been waiting in vain for the kale-avocado Mcflurry. Damn you, Ronald.

Bad choices would seem to lie at the heart of many things in life, and health care is no exception to this.

Of course there are no absolutes, and there are plenty of patients of mine from the same zipcode as Harry that I have broken through to. I’d like to believe this is because of something special I did, but its easy to recognize these patients as folks who were looking for someone to engage with. I just happened to be Johnny on the Spot.

So when I read about care via black barbershops, I was intrigued. The premise that barbers are peer influencers that may have more currency with Harry than the average brown man in a white coat waiting in a clinic is a good one.

The study screened for black men at barbershops who were regular patrons (≥1 haircut every 6 weeks for ≥6 months) with blood pressures at two separate screening visits > 140mmHg. Men were randomized based on their barbershop. Initially the study was powered based on the assumption that 10 barbershops would recruit 25 men each. Because the total number of patrons per barbershop were significantly lower than expected, the number of barbershops were increased and low enrolling barbershops were clustered into groups.

Of the 4500 black men screened, only 10% made it to their second screening blood pressure check in the intervention arm. Most of the dropoff was because many did not have elevated blood pressures on their first visit. Of the ~500 that made it to their second screening visit in the intervention arm, 25% had a systolic blood pressure < 140mmHg on their second visit, 25% were lost to follow up, and 25% declined participation in the intervention arm. In the end the intervention group was left with 139 men with uncontrolled hypertension.

78 barbershops began the trial, 26 (35%) were ultimately excluded because they enrolled 0-1 patients. One of the barbers exceeded expectations by enrolling four times the number of expected participants, and perhaps as a result has one more publication in the New England Journal of Medicine than I have (fourth author on this study). It may be that not every barber and barbershop are equivalent as peer influencers when it comes to hypertension or it could be that the barbershop clienteles differ in their receptiveness to discussions on health (by zipcode?).

The original trial design called for barbers to measure blood pressures and recommend follow up with pharmacists. The pharmacists were to meet with participants at barbershops, encourage lifestyle modifications and prescribe medications via protocol. Unfortunately, the barbers proved inconsistent in measuring blood pressures (they do have a day job after all), and the pharmacists had to take over measuring blood pressures midway through the study. The protocol was also adjusted so pharmacists could use a point of care lab assay to monitor electrolytes and renal function to save participants from trips for labs.

Though the trial was intention to treat, and retention in both arms was fairly good, the intervention arm did have seven patients lost to follow up. We know nothing about their blood pressures at 6 months, and we also know nothing of the clientele of the 26 barbershops that were unable to recruit more than 1 patient.

The results in those ultimately completing the trial were impressive – an average of a 27mmHg drop in the intervention arm compared to a 9mmHg in the control arm relegated to standard of care at 6 months.

Recall, however, that the point of this trial was to assess how effective barbers could be at changing behavior. The news here is mixed. Twenty six of the barbershops were ineffective at recruiting more than one patron. Fully two thirds of the patients eligible for blood pressure control did not follow up despite a variety of supernormal inducements present to participate – vouchers for haircuts, money for pharmacist visits, exhortations from peer influencers, and care delivered at a location administered by two full time pharmacists.

It is entirely likely, that the expanded screening did identify a group of motivated black men that has stayed out of clinics like mine. But Victor already showed this with his study in 2007. This particular study needed to show the feasibility of barbershop/barber- directed blood pressure control. It, unfortunately, did not quite do that. This study essentially shows that a health care system that moves itself into barbershops is effective in one third of men found to have poorly controlled blood pressure. I’m also fairly sure a pharmacist in my living room will improve my lipid profile. And it bears repeating, that despite this herculean effort, two-thirds of black men chose not to connect with a healthcare system that was in their barbershop. You can go ahead and put money on the odds that Harry White remains out of reach – its one you’ll win 66% of the time. I’ll also point out the study duration was six months – Harry had shown up like clockwork for 6 months after his stroke before disappearing.

No trial is perfect, but the hype that surrounded this trial given the limitations would have made MGM proud. One would think the terrors of evidence-based medicine that routinely devastate pharmaceutical companies for things like unplanned protocol adjustments are silent about protocol changes clearly designed to increase the size of the treatment effect of the intervention.

Regardless, I’m not an absolutist, and applaud the achievements of the investigators in doing important work to improve the lives of members of a community that disproportionately bear the ravages of uncontrolled hypertension.

I do take issue with this idea being sold as a scaleable, practical solution for many. In most spaces, intriguing ideas that don’t have a working business model die. In health care policy, however, there is no such thing as an idea that can’t be funded. Academics dream up interesting sounding constructs that satisfy a certain value system, and politicians follow through by assigning money they don’t really have to these bloated edifices.

This particular model is an especially impractical one: two full time pharmacists with the ability to get labs at the point of care only focused on hypertension for 180 men? In the future, I suggest one nurse practitioner for prostate cancer, one physician extender for atrial fibrillation, and at least two providers for diabetes. It should strike most as absurd that after dismissing and destroying the ability of the neighborhood doctor to survive, policy makers would rush to believe innovation comes in the form of an assortment of providers working in barbershops. I understand that there may be a deep rooted distrust of the healthcare system rooted in America’s segregated past that may need to be overcome, but this is best done by having one of the barbershop patrons be a physician with an office down the street. That this has not happened organically in underserved communities to date is a matter that merits discussion, but there should be little debate that policies most recently forwarded by liberals has snuffed out the independent physician.

While health care access is far from ideal, the idea that there aren’t health care options for poor underserved communities requires some context.

Hospitals in Philadelphia

There are five major academic hospital centers located in the city, in addition to a host of smaller community hospitals that take care of patients regardless of insurance in their inpatient facilities. For those underinsured or uninsured patients that can’t get access to the nonprofit academic medical centers outpatient facilities, a bevy of well scattered federally qualified health centers with physicians, nurses, social workers, and case workers awaits to deliver services for free. It may not be at the white glove level of a pharmacist in the barbershop, but it is certainly far from a desert of health care options.

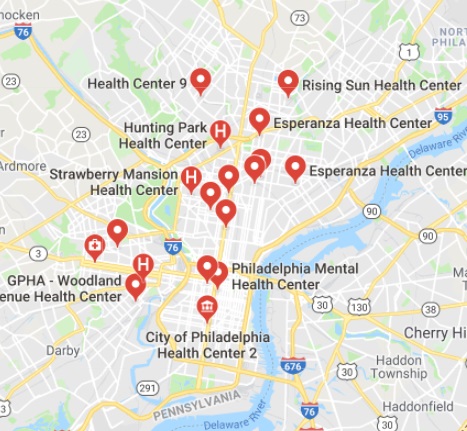

Health Centers in Philadelphia

Harry’s problem is that he has bought into the idea that he has as much control of his own health as a twig being carried by a stream. While appreciating the disadvantages the circumstances of birth has to offer, it seems unlikely we will make folks active players in their own health through interventions designed to promote passivity.

There are no easy solutions to healthcare disparities centuries in the making. The brilliant W. E. B. Dubois, addressing the plight of the black community in 1906 wrote: “with improved sanitary conditions, improved education, and better economic opportunities, the mortality of the race may and probably will steadily decrease until it becomes normal.” It strikes me that Dubois understood that better health was a result of education and wealth. One hundred years later, our obsession with healthcare threatens the economic health of the nation. Moving healthcare into barbershops may get us closer to some patients, but moves us ever further away from the efficient, effective health care system we all want.

Anish Koka is a cardiologist practicing in Philadelphia. He can be reached on twitter @anish_koka

from THCB http://ift.tt/2puBBGj

Rose

Rose

0 comments:

Post a Comment